Putting the Science into the Reading

A Brief Exploration of the Science of Reading and How it has Changed How We Approach Reading

In recent years, you may have heard or read some news about the Science of Reading. This is actually not a recent or a new phenomen, but an extensive body of research spanning decades that encompasses the branches of psychology, linguistics, education, and neuroscience.

Especially with the recent advancements in technology and research, some of our previous understanding about developing language acquisition and reading have been debunked, some of it confirmed, and much left to yet to be discovered.

One thing is crystal clear: the more we find out about reading, the more we realize that reading does not automatically happen when you put a book in front of someone. The Science of Reading emphasizes that reading is a rather complex process involving many parts of the brain, as well as readiness and active participation from the learner. Agency from the learner is a necessary component in the learning that involves the learner, whether it is reading, playing a sport, or even learning a life skill.

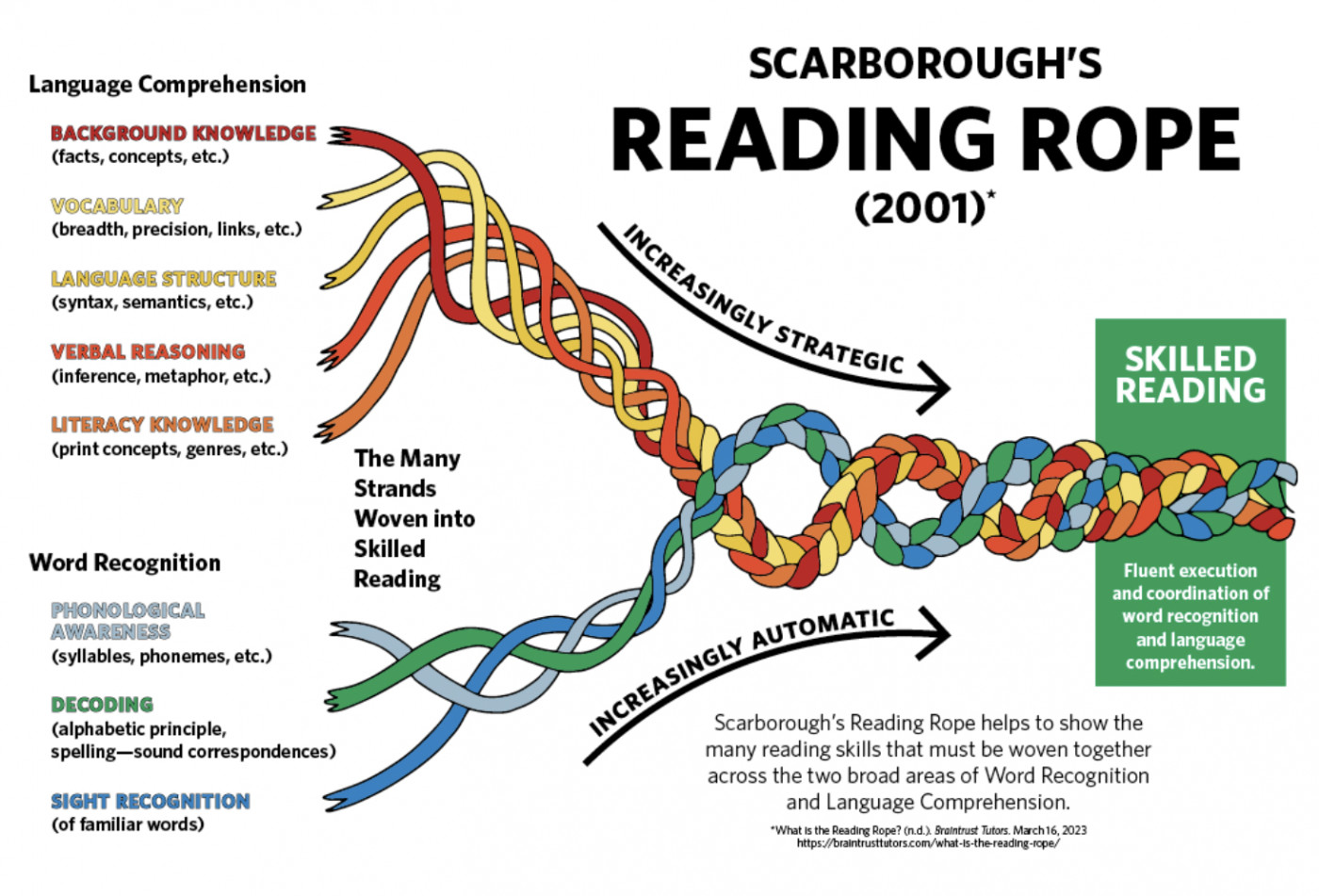

A big part of our current understanding of the Science of Reading comes from a body of research by Dr. Hollis Scarborough and colleagues that demonstrates the very complex and interconnected nature of reading in a visual format.

Commonly known as Scarborough's Reading Rope (2001), this model emphasizes that all aspects of language and literacy development are necessary for reading. Think of reading like a rope made of many smaller strands listed on the left side — vocabulary, structure, sounds (known as phonemes) and so much more. When all strands in the Reading Rope are in place and working together, the end result of skilled reading becomes strong. If any of the individual strands are missing, however, the Reading Rope will be impacted. This means that the reader will face challenges in achieving success in reading.

For example, consider the following sentence.

The sheep think of the flock when entering the pen.

If you have never heard of the word “flock” before, one may think that a flock can mean a shepherd or a sheepdog, as such substitutions still make sense in the context of the sentence. Also, if you did not know the short vowel sound of “o” in flock, you may read it as “fluke”, which means "coincidence", which once again, changes the meaning of the sentence.

Even the word “pen” can be confusing to a reader who may not know that this word has meanings beyond the writing instrument. In a singular sentence such as above, the background knowledge, vocabulary, language structure and phonological awareness, along with the sight recognition of familiar words are all activated in order to read and make meaning of it. This is why your child’s teacher will spend time on teaching phonemes, vocabulary, and language structure, alongside reading stories with the students — because all aspects are needed for an actual understanding of the text.

The Simple View of Reading also echoes the importance of both decoding and comprehension aspects of reading. It notes that:

“Decoding (D) x Language Comprehension (LC) = Reading Comprehension (RC)”

The most important part of the Simple View of Reading is within the formula, however, is the multiplication factor, and how that affects the likelihood of reading success Goldberg (2023).

It echoes Scarborough's Reading Rope with the idea that reading success rate depends on both decoding and comprehension working together.

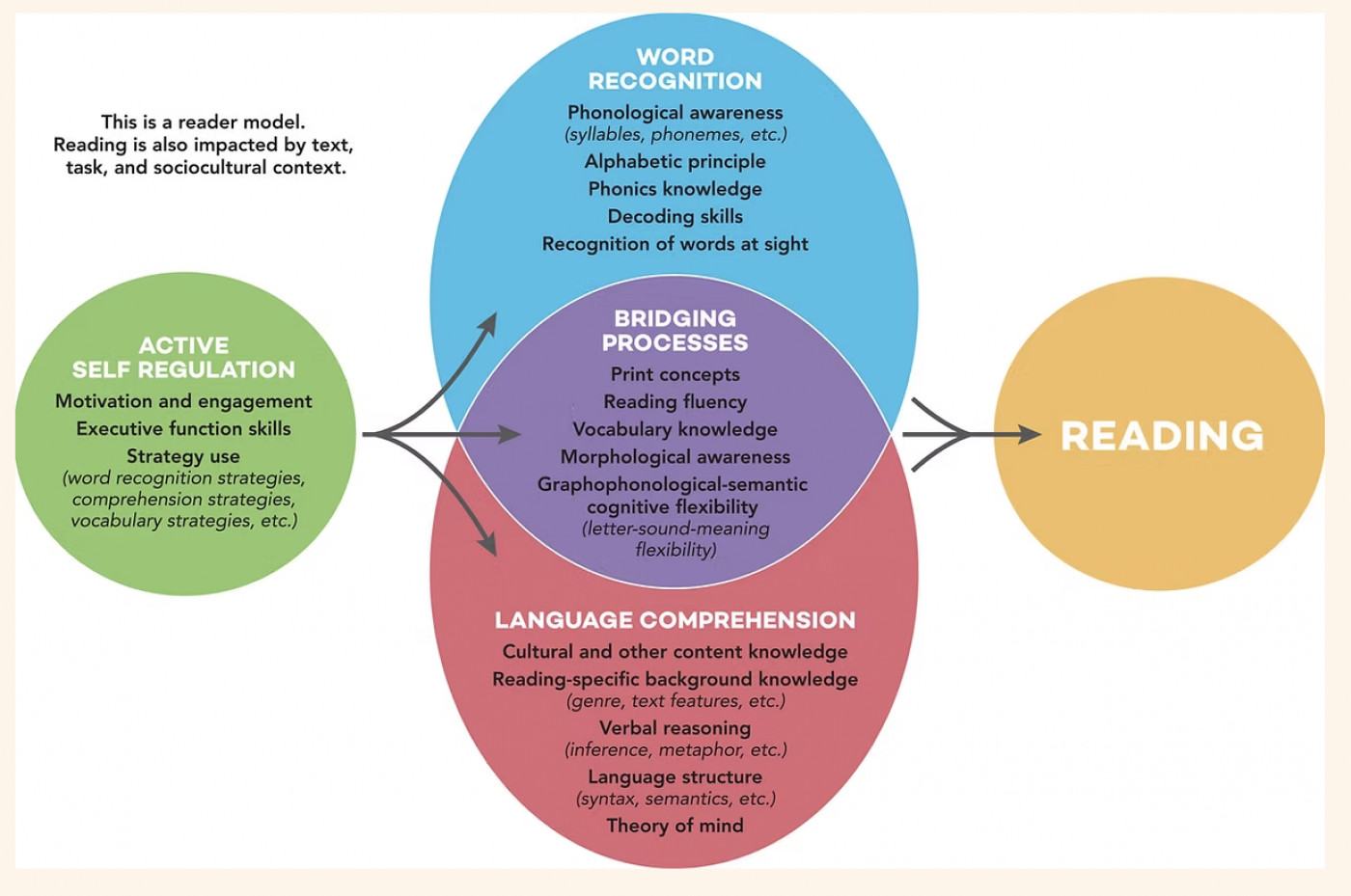

A more recent research called the Active View of Reading emphasizes that reading, like much of learning, is an active process. And that it starts with the readiness from the learner, including their motivation and executive function fully functioning, to engage the student in the learning process.

With inspiration from Scarborough's Reading Rope, this model of reading explores the complexities of reading further by including cultural and content contexts, cognitive flexibility, word structures (also known as morphemes), and much more as the necessary components towards reading success.

The updated English Language Arts and Literature (ELAL) curriculum from Alberta Education, used here at The International School of Macao, also reflects the recent research and evidence-based changes in how literacy should be approached by educators in schools. The Organizing Ideas, or the main strands, of the ELAL curriculum include Text Forms and Structures, Oral Language, Vocabulary, Comprehension, Writing, and Conventions for all grades; with Phonics, Phonemic Awareness, and Fluency mainly emphasized in the younger grades. Reading was purposefully not categorized as a singular Organizing Idea or a strand, as it involves many of these other facets of literacy, as discussed above starting with Scarborough’s Reading Rope.

As we work with our student population, the majority of whom speak English as an additional language, it’s important to keep in mind that we need to get to know the students as readers first. Using well-known screeners, such as the Alberta Education early years literacy screeners, Acadience Reading tools (adopted from DIBELS from the University of Oregon), and MAP Growth provide us with a preliminary triangulation of data about our students’ reading readiness, skills, and abilities. In addition, our skilled teaching staff teach the ELAL curriculum and support student literacy and reading development while gathering continuous data to provide targeted support as needed.

Reading does not happen by chance or fluke, as demonstrated in the Science of Reading. It is a complex process, which requires explicit instruction, active learner engagement, monitoring, and guided support to ensure a reading success. At home or school, young readers (and older readers new to the language) need to be provided with adult guidance and support. We do this by fostering a love of reading, supporting learners to face and overcome challenges, and celebrate growth together in all aspects of their learning journey, including reading.

---

References

Alberta Education. English Language Arts and Literature (Alberta’s Curriculum). 2023. Alberta Education. https://curriculum.learnalberta.ca/curriculum/en/c/laneng6?s=LANENG

Dehaene. S. (2024). Eyes on Reading: Dr. Stanislas Dehaene with Emily Hanford. Planet Word. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_4NWaTw36i8

Duke and Cartright. (201). The Active View of Reading. Early Literacy Research, Policy, & Practice.https://www.nellkduke.org/the-active-view-of-reading

Goldberg, M. (2023). How Children Learn to Read, with Margaret Goldberg. Reading Universe. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DYBmMiIzcIo

Hoover, W., & Gough, P. (1990). The simple view of reading. Reading and Writing. An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2, 127– 160.

Lane. H. (2021). What is the science of reading? The University of Florida Literacy Institute. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cnkJ6VvDr2M

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. Handbook for research in early literacy (pp. 97–110). New York, NY: Guilford Press

Xu, B., Burns, J., Davis, B., Friesen, S., Guo, Y., Russell-Mayhew, M., Sabbagh, S., Schroeder, M., Wilcox, G., & Zhao. (2016). The nature of learning and the learner. Alberta Education, Government of Alberta.